My Photographic Time Tunnel - About Leica and Serial Numbers

It was and it’s still is a dream to hold a Leica camera in your hands and use it as a tool for taking pictures. Ever since I’ve started my Photographic Time Tunnel journey I was hearing about Leica cameras, held by legendary photographers such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Andreas Feninger and even the Israelis Alex Levac and David Rubinger. One story that captivated my imagination was about a Leica without a serial number. I’ve heard it from Aaron Gurevich, a camera collector I once met, who knew the owner of that unique Leica. The story, that sounds much like an urban legend, is about a Jewish war survivor who lived in Germany after WWII and was treated at the Red Cross hospital near Wetzlar. As a patient who was enjoying the benefits of the Red Cross health care, he was given a weekly amount of cigarettes packages. I believe that in those days they knew less about the negative effects of smoking, so this guy could enjoy the positive effect while relaxing on his balcony. Getting cigarettes in those post-war days was a very difficult thing, so one of his neighbors who had a hard time living without smoking, made a deal with him: The neighbor will receive one package of cigarettes a week, and in return he will give that Jewish patient a part of a camera, that he will steal from the factory where he was working. Luckily for the both of them, the patient didn’t need so much cigarettes and he thought that a camera could be a cool thing to have, so he agreed to go forward with his neighbor’s deal. And so the weeks passed, when one could smoke again, and the other collected camera parts. After a few months the neighbor requested a double package of cigarettes and in return he delivered the outer shell of the camera – the body. At the following weekend, with all the camera parts in hand, the neighbor sat and assembled the camera, exactly as he was doing at the factory. The camera was a Leica, and since it didn’t leave the factory doors as a product, it didn’t held a serial number. Many years has passed and the Jew left Germany and moved to Israel. By the late 70th he sold the camera to a photographer and camera collector by the name of Ezriel Kalman.

When I’ve heard that story I set a goal to meet Ezriel and get to the bottom of the tale. Ezriel Kalman has a little camera shop at King George Street in Tel-Aviv. I knew this place with its little display window, stuffed with old cameras, but it was always closed. I assumed it was one of those places frozen in time, waiting for some legal lawsuit to be settled between the children of the owner (I know a camera shop up in Herzliyya Main Street, which stands like that for the last 12 years. I even called one of the children so he might let me peek inside this time capsule, but he didn’t even want to hear what I had to say). Anyhow, I was informed by the friend who told me the story of the numberless Leica that the shop is not abandoned, and if I want to meet Ezriel I better visit the place early in the day.

I met Ezriel sitting in front of his shop, talking with the elderly by passers. He maintains a special corner with bowl of water for the dogs, which he loves dearly and has an informal dialog with. To my surprise it didn’t take long into our conversation, until he voluntarily told me the story of the numberless Leica, with some minor changes from what I originally heard. You know how those stories change from one teller to another, until you hardly recognize the specific details. But the story still contained a Leica and it didn’t have a serial number on it. I told Ezriel that I would love to see that special camera and try to make it work for my article, but he firmly said that he won’t take it out of the safe and that he is afraid that the people at the Leica Company will hunt him down for it. I was a little bit disappointed, although the whole time I suspected the story was too good to be true. Ezriel noticed the disappointment in my eyes, and said he has a better Leica to show me. How could it be any better? Well, it was his father’s Leica, which he bought in Bucharest at early 20's. Actually, I prefer to see and renew a camera that served a few generations of the same family. We scheduled a meeting for the next week, so Ezriel will have time to dig some photos his Leica produced back then in the 30's and 40's. That gave me enough time to do some research about Leica – the Rolls Royce of cameras.

Well, Rolls Royce might be the wrong equivalent, since the story of the Leica is really the story of how film cameras became smaller and easier to use. Leica is actually all about being more compact and accessible (If you’ve got the money to buy it). It all started with an optical engineer by the name of Oskar Barnack, who worked at the Ernst Leitz Company. Oskar loved photography, and the story says that he suffered from asthma and had difficulties carrying all the heavy photography equipment to shoot outside, so he was experimenting with minimizing the camera equipment and film. In those days, I mean 1911, everything was huge (Equipment and the size of film), so making it smaller was an essential part in evolution. Oskar Barnack wanted to utilize the standard 35mm film used by Edison and the Lumiere brothers for the movies industry, and instead of using it vertically as in fast running film cameras for the moving pictures, he placed it horizontally in the stills camera, making a frame of 24x36mm picture size negative.

It took Oskar many years and some prototypes until the company authorized the manufacture of his first 35mm camera, and in 1925 the first batch of cameras where commercially available to the public. Ernst Leitz Company called them Leica, which is taken from the words Leitz Camera. The small camera was a great success – so small in size, it was all that Oskar Barnack meant it to be – a camera you could take with you outdoors and take pictures while having fun. Today we are used to small size cameras combined even in our cellphones, enabling us to snap as much as we want, but back in 1925, a camera so small was a great invention and the beginning of a new era in photography. An American advertising poster from those years showed that the Leica fits inside the shirt pocket, and announced that this is the “Camera of the Future”.

“Leica II” that came in 1932 was another leap into the future, with the extraordinary Rangefinder mechanism incorporated into the camera. That made the Leica even better, making it easy to focus the lens on the subject. Today we take things like comfortable camera size and easily to achieve focus for granted, but in the early 30's of the 20th century, these innovations where truly a great leap. With these new tools in the market, a new generation of photographers emerged with the art of Journalism and Street Photography.

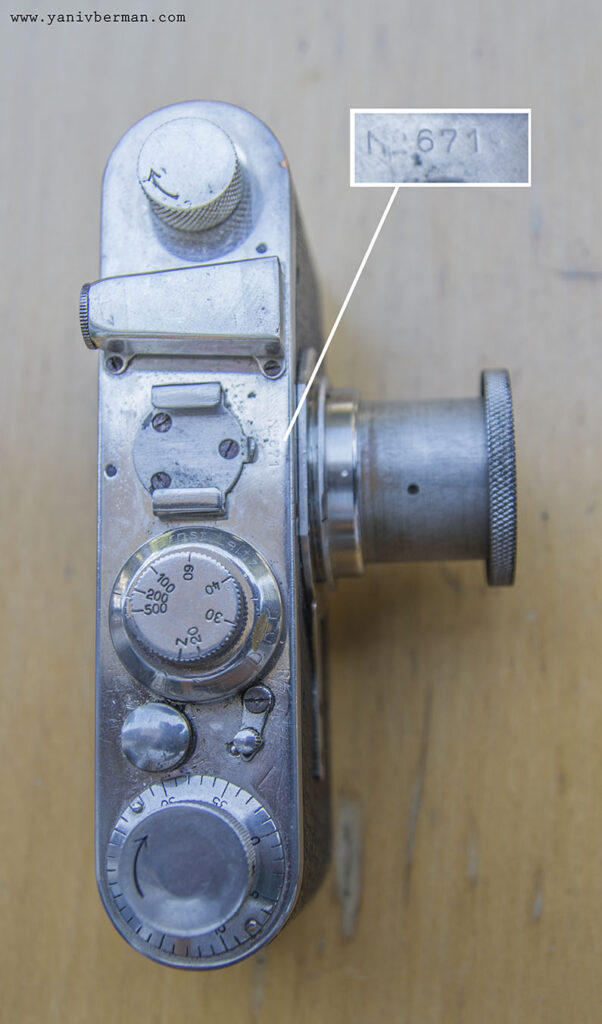

I didn’t know what kind of Leica Ezriel’s father bought in Bucharest, but after getting all this information on the history of Leica, I was ready for a surprise. Any Leica camera could have been a treat, but when Ezriel unfolded the camera from her warn leather cover I couldn’t be more amazed. Not only was it a “Leica I” model, the serial number engraved into the metal body of the camera showed a three letters number: 671, which means this camera was from the very first batch of 870 Leica cameras made in 1925. “Is it still working?” I’ve asked Ezriel with a slight thrill in my voice. “Yes” he said, a little surprised by the question, “Like always”.

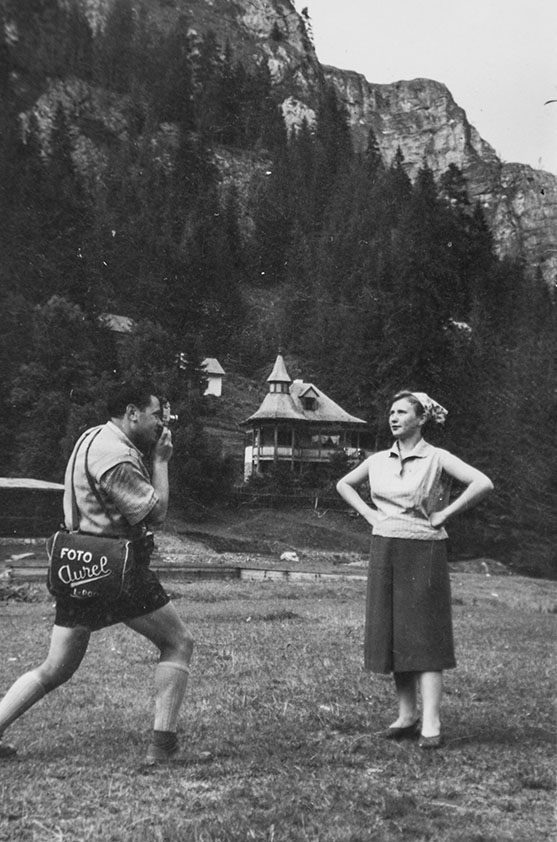

I was eager to try the camera out, but Ezriel seemed reluctant to let the camera out of his hands. In the process of gaining his trust I questioned Ezriel about the history of his camera. Ezriel was born in a little village in Romania called Hârlău (in Moldova) where his father owned a successful photo studio. In those days the custom was to attend the studio and have your whole family engraved on photo paper by a professional man. Ezriel’s father that always thought about new ways to expand his business, heard about the new German invention called “Kleines Bild Film” which means “Film for small pictures”, and took a trip to Bucharest where he had a chance to purchase the magnificent Leica. The idea was simple: on the weekends Ezriel’s father took the Leica to the center of the village where people used to hang, and he photographed them at the street or at the park. Since film could only be developed much later at the studio, each potential client received a card inviting him to come and buy his photo. This line of business was very successful, and soon enough, Ezriel helped his father on the weekends and holydays taking the “Street Photos” himself. The Second World War came, and the Jews of Hârlău had hard time making a living. Ezriel couldn’t go to school, so his father decided to educate him with his own profession. After his father death in the early 60's, Ezriel left Moldova and came to Israel, where he opened a photo studio. Though he didn’t use the old Leica anymore, it still has an honorable place in his ever growing old cameras collection.

In recent years, long retired Ezriel Kalman enjoys coming to his little shop every day and occupy himself with buying and trading cameras for his collection. In the few hours I stayed with him in front on his shop on King George Street, only one woman stopped to ask if he is interested in buying her father’s old Rolleiflex. Many other people came to chat with Ezriel on topics ranging from politics to the Olympic Games, or have their dogs enjoy some cool refreshments. I guess it is a great way to pass the time when you’re retired…

It was almost noon and Ezriel finally realized that the only way he could get rid of me was if he would let me load his camera with film and have a little fun with it. I had an idea, why not recreate the old days of street photography and take photos of by passers as if they are potential clients and would come later to acquire their photo. Ezriel, now a little bit tired, agreed to play along, and as in happened, he even enjoyed it.

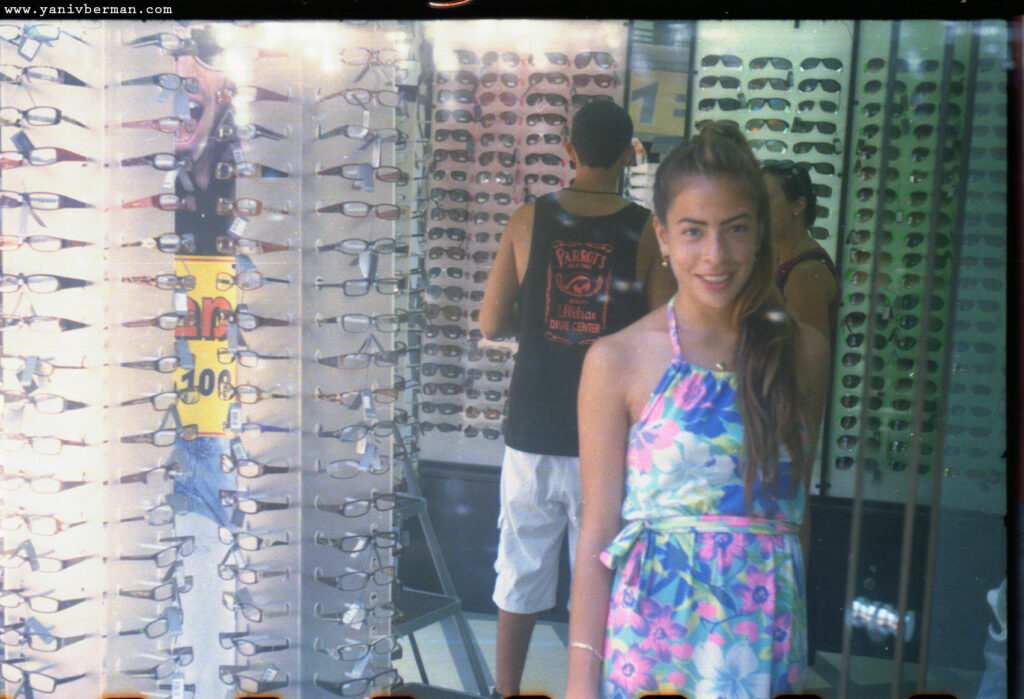

Loading the “Leica I” with regular 35mm film turned to be more problematic then I anticipated. In this early version of Leica you have to remove the lower cover of the body and insert the film to the exact location behind the shutter. Though Ezriel camera was a German Leica that could stand the wrath of time, it still had 87 years behind it, and thus rejected our efforts in loading the film. Ezriel had an Idea. He unscrewed the lens and helped the film to its place by shoving it while the shutter was open (The camera has a Z option for having the shutter constantly open). While the lens was out, I had time to check it out, and realize the condition of it. The lens is a 50mm f/3.5 Leitz Elmar made especially for the Leica by Professor Max Berek, who adapted the Cooke triplet photographic lens patent (From 1893) that managed to eliminate most of the distortions (at the outer edge) lenses of the time had suffered from. The lens had no coating (that was applied to commercially sold lenses only after WWII), and since it hasn’t been cleaned for at least 50 years it was very foggy and had some ugly spots on it. Either way I was happy to see what it has in store for us. Nowadays people use all sorts of different filters to make photos look like they were made 50 or 100 years ago (we all do it on Instagram), so why not having the real deal?!

After succeeding with film loading, Ezriel suggested that we adjust the aperture to f/9 and the shutter speed to 1/200. We took turns with the camera and placed our faith on the good nature of the Tel-Avivians crowd. It wasn’t easy, since people today tend to take a better care of their privacy, but some easy going spirits donated their bodies for the sake of old time analog photography. As always, I’m using modern Fuji color film, in contrast to the old camera. Here are some photos that came out from the Leica's belly:

I wish I could have more time with Ezriel Leica. Running along with a camera like that could lead to great adventures. But what can I do?! This Leica, with that unique serial number, belongs inside a safe or a museum. I really should learn how to settle with my father’s old Yashica and the DSLR Canon… They are not royalty equipment, but as Ezriel said to me when we just met, it’s not the camera that makes the photo, but the men who pushes her buttons. He is right of course. Cameras are just tools… But we humans need inspiration. And challenge. What will be the next challenge for me now, after writing about a first model Leica? Who knows…?