My Photographic Time Tunnel - Rolleiflex Original Standard

I was making a video about the exhibition of the pioneer photographer Avraham Soskin when I saw it for the first time. She was hiding under hard glass, protected from the touch of human hands. It was out of reach – a museum artifact. It was Avraham Soskin’s old Rolleiflex.

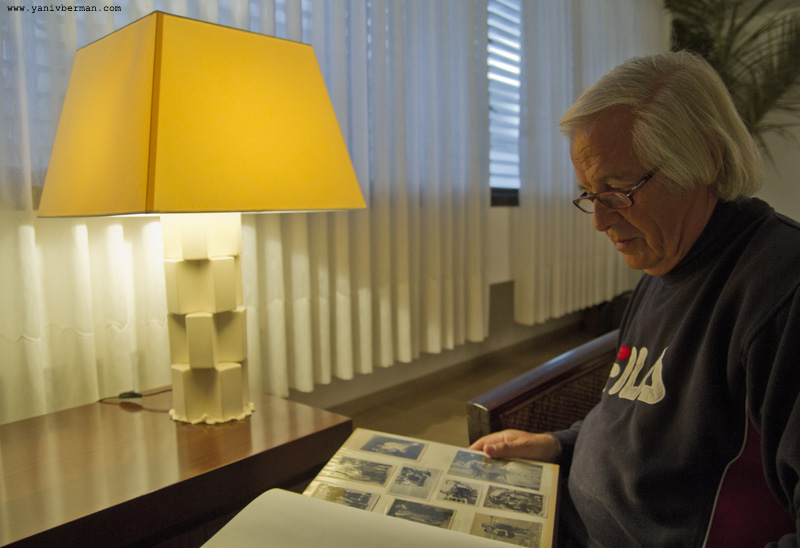

About a month later I met Rani Soskin (the grandchild of Avraham Soskin) in the museum, and he asked me to send him a copy of the video I made. Only when I received a mail from him saying that he liked the article, I got bold enough to ask if I can try to take some photos with his grandfather’s camera. To my surprise he thought it was a good idea, and we scheduled a meeting.

The Herzlilenblum museum for banking and Tel-Aviv nostalgia was established by the Israeli Discount Bank in a restored building on Neve Tzedek Quarters. Since I work with the bank for many years, I have close relations with the museum manager (Yudith Ben Levy) and curator (Irit Fenig). When I asked for their help they gave me complete access to the show rooms. In fact, they were very excited to see if this old camera could come back to life.

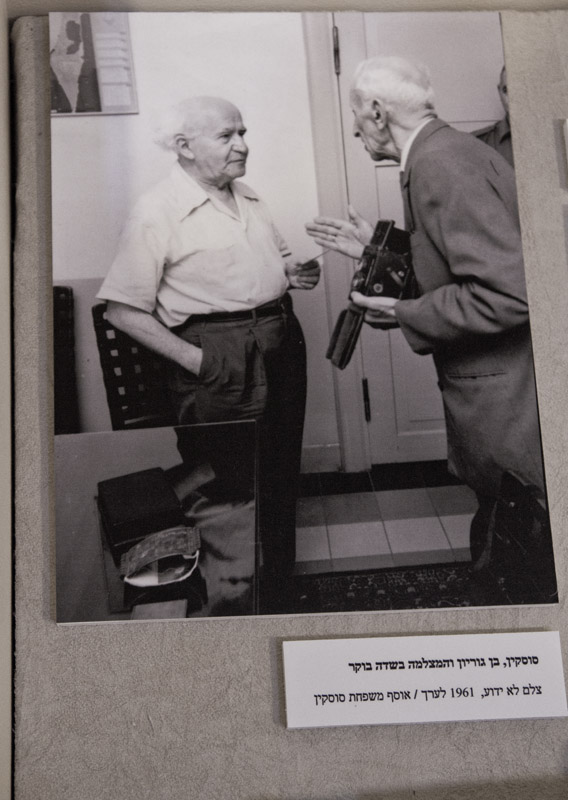

Before the meeting with Rani Soskin I had my doubts. Avraham Soskin traveled from Russia to Palestine in 1896 and opened his first studio in Jaffa. When Tel-Aviv was founded in 1909 he moved to the New Hebrew town, where he worked for more than 50 years, taking thousands photos of the city he loved. My guess was that he bought the Rolleiflex in the early 40th, for shooting outside the studio. Soskin died in 1961, and left his belongings to his grandson, Rani, who never used it again. So this Rolleiflex hasn’t been in use for 50 years! It was a solid guess that the camera doesn’t work.

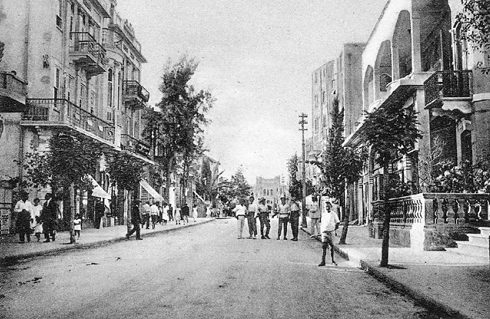

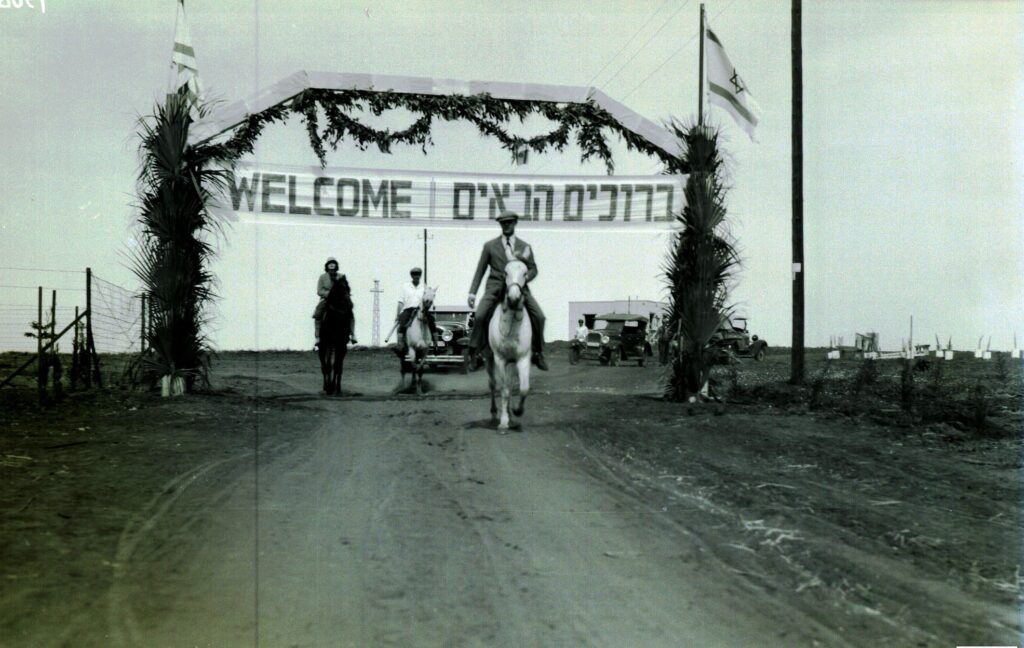

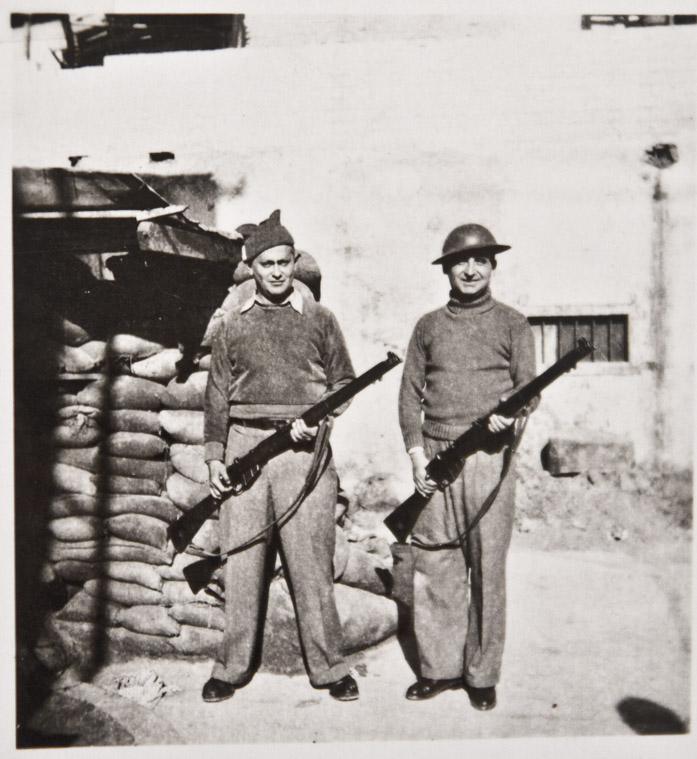

(Photos Soskin took in the early years of the 20th century)

Working or not, I had to fight my way to revive the camera. I held my breath while Irit Fenig, the curator of the museum, took the camera out of the glass cabinet and placed it in my hands. You have to understand that Soskin is Israel’s most historically acclaimed photographer, and the camera I was holding in my hands was his personal working tool. I was very excited about it. I sat to the table in one of the office rooms and peeled it from the leather casing. The moment of truth has arrived. I tried to cock the shutter release knob, but it didn’t lock. I moved it back and forth but nothing happened – the shutter didn’t budge. We were all very disappointed.

I was ready to leave the museum with the promise to ask the advice of the elders of Allenby street vintage cameras workshops, when Irit asked me if I care to take the camera with me and try to fix it. Well, of course I was willing to do that, but I wasn’t sure Rani Soskin would agree to let the camera out of the museum perimeter. I was wrong. Apparently Rani had his trust in me, and he agreed to let me go on with this little adventure. Later he told me that he believe his grandfather would rather see his camera work again than sit useless.

I was walking the old streets of Tel-Aviv: Lienblum St., Kalisher St., Nahalat Binyamin St., Allenby St. – and I could feel Soskin there with me. After all, I took his old Rolleiflex. Tel-Aviv has changed deeply in the past 50 years, and I wasn’t sure if he would approve this change, or me taking his Rolleiflex…

Allenby Street goes all the way to the beach, and right there, just before you reach the promenade, there are three old stores with a lot of old cameras. I do my best to keep good relations with the owners of two of them, though only by writing these words I may be fracturing the delicate fabric of their pride. As you can probably understand, the three stores circulate the same almost gone business, and fight over a very thin crowd of clients. First I went to visit Nahum Guttmann, the old photographer and camera merchant. Guttmann came to Israel in the late 40th and worked for many years as a journalist photographer, before settling in a little store, selling and buying used camera equipment. I love the man for his photos, and I respect his advices, though he is no technician. Together we tried to operate the old camera, with no further success. It took me more than an hour to get out from his store. Guttmann plays a fundamental part in the photographic history of Israel, and has some amazing stories to tell.

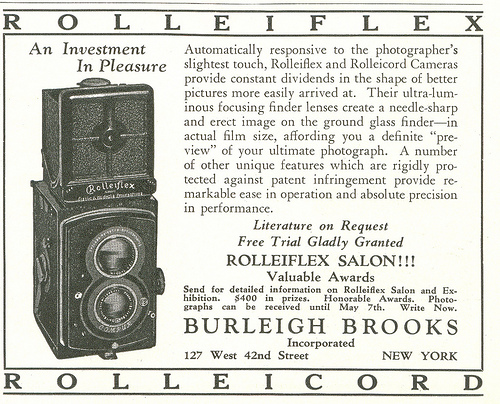

Guttmann suggested I’ll try my luck with a store called ‘The golden camera’. I had never been there before in my life, always preferring his rival on the opposite side of the street. But I felt this camera deserved a complete checkup, so I took Guttmann’s advice and entered the glass walled store, stuffed with old cameras I could only dream to shoot with. I hit the little bell on the front desk and waited several long minutes for the manager to come. When he came, he looked at me behind his technician metal magnifying glasses, showing me in his way that he can’t spare me much time. I showed him Soskin’s Rolleiflex and asked if he could fix it. “This is a unique model” he told me immediately, and he searched for the model mark on the body of the camera. Finally he came to the conclusion that this model carries no sign or mark. He disappeared into the dark of his store and when he came back he placed on the desk the greatest camera catalogue I’ve ever seen. We identified the model of Soskin’s Rollieflex by the special design on the head of the Finder, shaped like a cross, and the aperture of the taking lens (Zeiss Jena Tessar f3.8). I was truly surprised to see that this camera model (The original old standard) is dated between the years 1932 and 1935. With this information I was more eager than ever to make this camera work. But the man behind the desk reminded me again that he didn’t have much time, and that I’m invited to leave this treasure behind. I told him that this is not my camera, and it has to get back to the museum in one hour. He wasn’t too impressed. Apparently he wasn’t caught by my excitement over the old camera.

I was down to my last resort – Photo Doron. I found Doron inside his little full of used camera equipment store, dissembling Sony video batteries in order to learn how they work. I know him for quite some time now, ever since I got this analog photography bug. He, for one, has had enough of me. I come a lot, I show him damaged cameras, I ask for his advice – but only rarely do I buy something or let him fix a camera. A real nuisance… “Now hold on”, I told him before he had time to dismiss me with the wave of his hand, “Just look at this”. Doron lowered his spectacles and took a long look at the Rolleiflex. “Can you fix it?” I asked him. He could, but he wanted me to leave it and come back later. I couldn’t. Not this time and not with this camera. We haggled for a while and agreed on the fee. I had one condition, though. I wanted him to let me film the process.

Remarkable! This 80 years camera came back to life. Some oil, a little dusting and the mechanism is moving like clockwork. With a working camera in my hand, loaded with 120 Kodak 160NC roll, I went to do some tests. It took me some time to understand all the details of how to operate the camera – How to rotate the handle between shots, where the shutter speed and aperture indicator is situated. I think I was so happy to see the shutter blinks again, that it was hard for me to concentrate on the task. Finishing the 12 photos just in time before the museum closed; I placed the camera back in the show room, and strolled to the lab. At this stage of events I already knew it will turn out just fine, and I was making phone calls – next week I’ll have another shootout, and I’ll make this camera deliver wonderful photos.

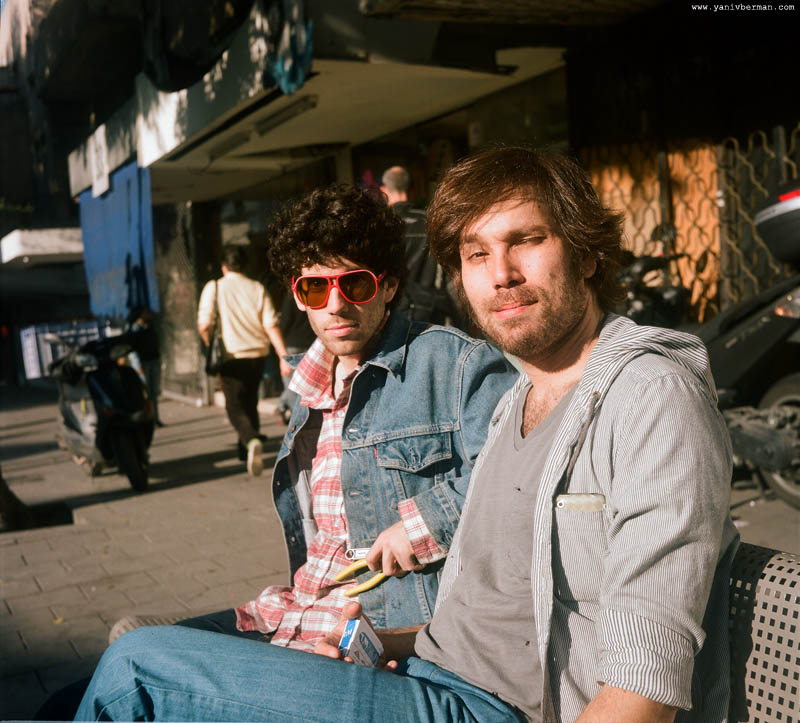

Photos from the test shooting, taken in Tel-Aviv

Now that I knew the exact model of the camera, I could prepare to the shootout and do some research. Rolleiflex is a twin-lens Reflex camera (TLR) made by a German company founded in 1920 by Paul Franke and Reinhold Heidecke. Rolleiflex cameras were very popular, used by professional photographers all over the world. They use Medium Format film, measured 6 by 6 (centimeters), which was the common film size of the time, until the late 50th when 35mm film took over, leaving the Medium Format to professionals seeking higher detailed photographs for various uses. The idea of the two lenses built on the front of the camera is that the photographer view the landscape through the upper lens, and the photo is taken with the lower lens which sits right behind the shutter and film. The two lenses are synchronized so the focus that is set through the finder goes to both lenses. This twin-lens patent was a hit, and Rolleiflex was awarded the Grand Prix at the World Exhibition in Paris, 1937.

Avraham Soskin’s Rolleiflex is the Standard 621 (Probably dated to 1932). It has a Compur Rapid shutter that goes as fast as 1/300. The taking lens is a 75mm Carl Zeiss Jenna Tessar, with f/3.8 aperture. Though a lot of specifics changed over the years, the genuine built of the Rolleiflex stayed the same. It is a very reliable camera and the fact that Soskin’s Rolleiflex still works proves it.

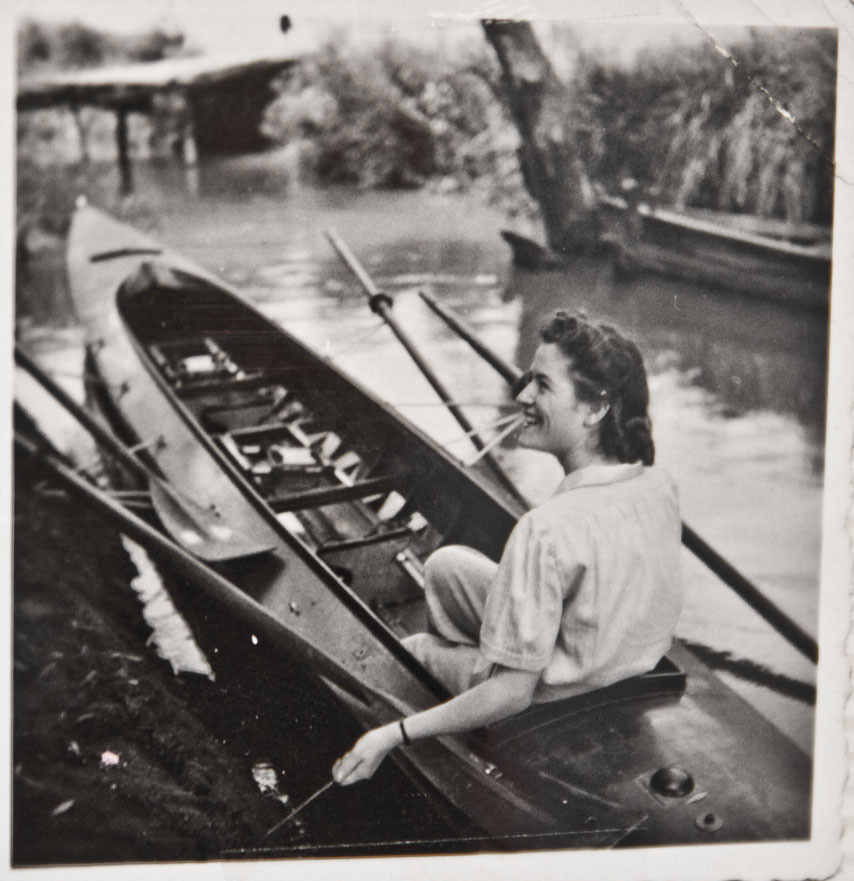

Here are some of Soskin’s photos, taken with his Rolleiflex:

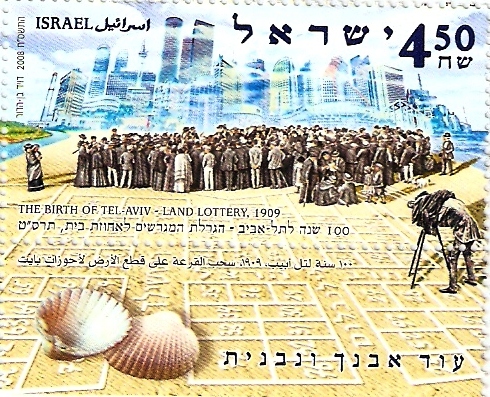

For the task of shooting with the Rolleiflex I called my friend and colleague Shahar Ziv. He is a producer and a very talented video editor. We invited the beautiful Ingrid Feldman to model for us, and she was happy to join our team, only for the thrill of the adventure. We had short time for the operation, so the best thing was to shoot at the Herzlilenblum museum. The place is very unique. The house was built in 1909 by the Frank family on the land they got by winning the famous seashell land lottery, done by the Ahuzat Bayit foundation in order to divide the land between the 66 founders families.

After many years of decay, the house at the corner of Herzl St. and Lilenblum St. was magnificently restored and made a museum. Using its rooms and halls for photography is a great idea and it fits with the old fashion style I wanted the photos to have. Ingrid brought a dress that resembles the style of the 20th and she was very patient during the long minutes she had to stand and pose while I did my light metering and focusing. Though Soskin himself used only black & white film for his photography, my style is different and I only use color; Two different approaches, done with the same camera, 50 years apart.

For the indoors locations I’ve used one roll of 120 Kodak color film, 800asa

For the second roll (160asa) we went outside to the streets of Neve Tzedek

After taking the last photo it was time to say goodbye. Soskin Rolleiflex proved its capability to take photos after more than 70 years of service, and now it was time to place it back under glass and neon lights. People go on with their lives, getting older, while a camera like Avraham Soskin’s Rolleiflex stays locked in time. I hope the light will blink again through the taking lens, and future photos will be made. A camera is like a time machine, collecting photos through the ages. Humans, on the other hand, walk on the flat line of history, having to take one step at a time. Soskin’s Rolleiflex enabled me to take a look at the past, and I used it to mark the present. Now these new photos are in the past, but the future film rolls are there, waiting patiently for their turn.